Jon Levitan is a student at Harvard Law School and a member of the Labor and Employment Lab.

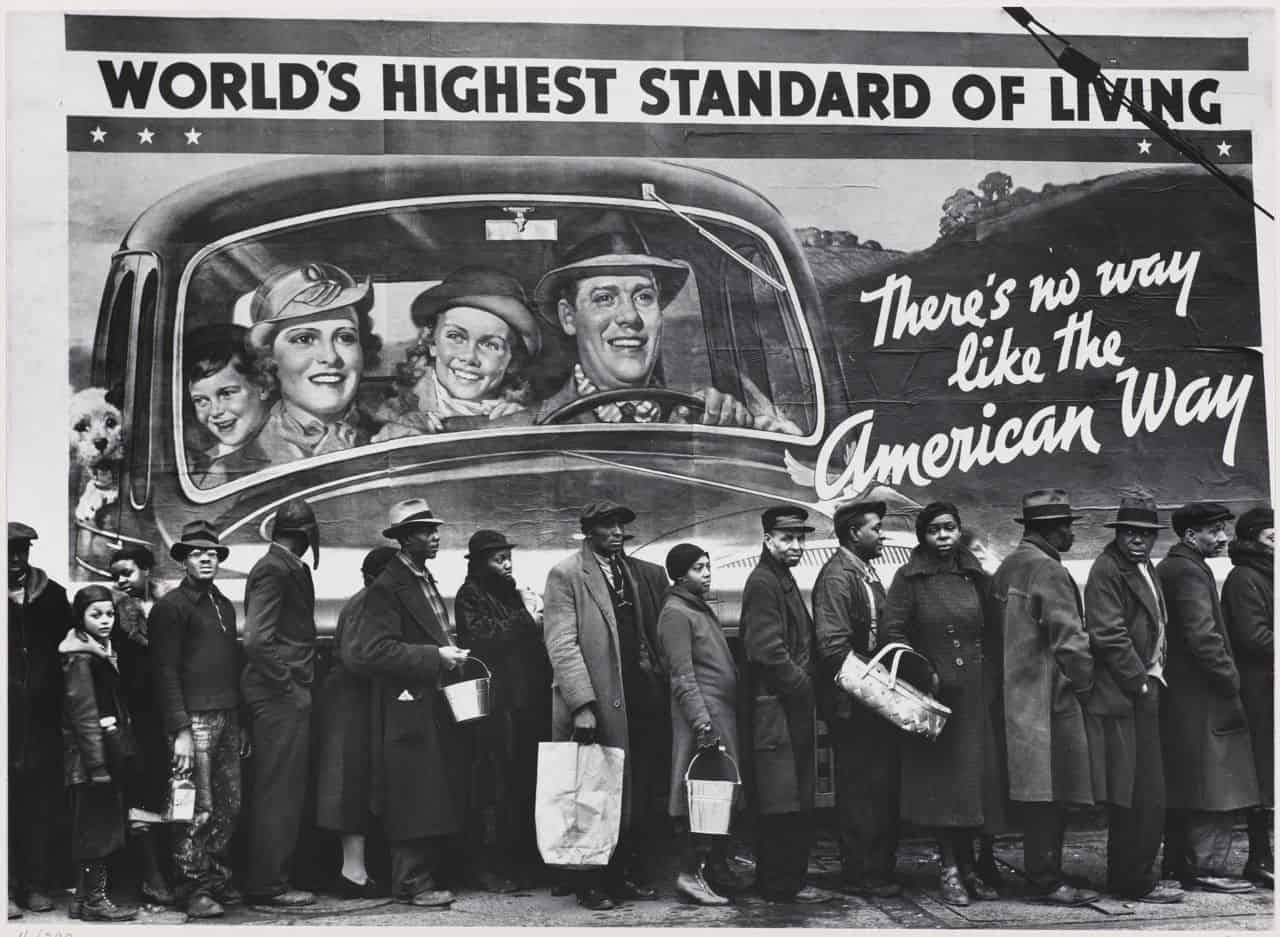

Tens of millions of Americans are still out of work and relying on expanded unemployment benefits, but not all jobless workers are receiving those benefits. And the distribution of unemployment benefits, like so much else about American society, is infected with racism. According to data published by ProPublica, significantly fewer unemployed Black Americans (13%) are receiving unemployment benefits, compared with unemployed white Americans (24%). William Spriggs, a professor at Howard University and Chief Economist for the AFL-CIO, said “in every recession, we see these same disparities.” A report detailing the experiences of D.C.-area workers highlights a few ways that the unemployment system has failed Black Americans. Devonte Brooks, a 22-year old recent college graduate with $30,000 in student loans, had to wait 20 weeks to receive unemployment, instead building up credit card debt and draining his savings to get by.

Racial disparity in unemployment benefits is nothing new. Unemployment insurance, when it was first enacted during the New Deal, excluded farmworkers and domestic workers. According to the Propublica report, 80% of Black workers fell outside the scope of the unemployment insurance system at one point. As Marina highlighted last week, these exclusions, which appear in virtually all New Deal-era labor and employment laws, were “well-known to be a race-neutral cover for maintaining the domination of white supremacy in the South and excluding Black workers from labor law’s protection.”

The current iteration of the unemployment insurance system is so broken and dysfunctional that a distinct brand of politician is emerging promising to fix it: unemployed workers. Kelly Johnson, running for a seat in the Florida House of Representatives, began organizing fellow unemployment workers after waiting many weeks for unemployment benefits. “We felt like nobody at the top in Florida was listening to us,” she said. “So we’re doing it ourselves.” And injustice at work is driving others to work in politics, even if they are not running for office themselves. Daniel Stone, who was fired by Dollar General after sounding the alarm about safety issues at work amid the pandemic and then worked on a Senate campaign, said that “[t]he pandemic has completely removed the veil that companies will take care of us, because we work for them…[i]t’s time now to make them take care of us and protect us, through legislation and action.”

Yesterday was the first day of the Republican National Convention. If their opening night is any indication, despite the long-term decline in union density, the GOP still takes the labor movement seriously. Nikki Haley referenced a suit by the Obama NLRB brought against Boeing for moving jobs to South Carolina amid a strike, a move Haley supported as the state’s then-Governor. But it was who the Trump-led Republicans tapped to deliver one of the opening speeches that drove home the point: teacher Rebecca Friedrichs. Friedrichs brought the first constitutional challenge against agency fees to reach the Supreme Court, but her case fizzled out after Antonin Scalia died. She said last night that President Trump is “breaking the unions’ grip on our schools; that’s why unions have tried to destroy him since the day he was elected.” Friedrichs may have gotten a primetime RNC slot for betraying her union brothers and sisters, but it was Mark Janus, named plaintiff for the ultimately successful challenge to agency fees, who really cashed in: he is now a “senior fellow” for the Liberty Justice Center, the organization that bankrolled his suit.

Daily News & Commentary

Start your day with our roundup of the latest labor developments. See all

April 18

Disneyland performers file petition for unionization and union elections begin at Volkswagen plant in Tennessee.

April 18

In today’s Tech@Work, a regulation-of-algorithms-in-hiring blitz: Mass. AG issues advisory clarifying how state laws apply to AI decisionmaking tools; and British union TUC launches campaign for new law to regulate the use of AI at work.

April 17

Southern governors oppose UAW organizing in their states; Florida bans local heat protections for workers; Google employees occupy company offices to protest contracts with the Israeli government

April 16

EEOC publishes final regulation implementing the Pregnant Workers Fairness Act, Volkswagen workers in Tennessee gear up for a union election, and the First Circuit revives the Whole Foods case over BLM masks.

April 15

The Supreme Court ruled in favor of bakery delivery drivers in an exemption from mandatory arbitration case; A Teamsters Local ends its 18-month strike by accepting settlement payments and agreeing to dissolve

April 14

SAG-AFTRA wins AI protections; DeSantis signs Florida bill preempting local employment regulation; NLRB judge says Whole Foods subpoenas violate federal labor law.