Brianne Power is a student at Harvard Law School.

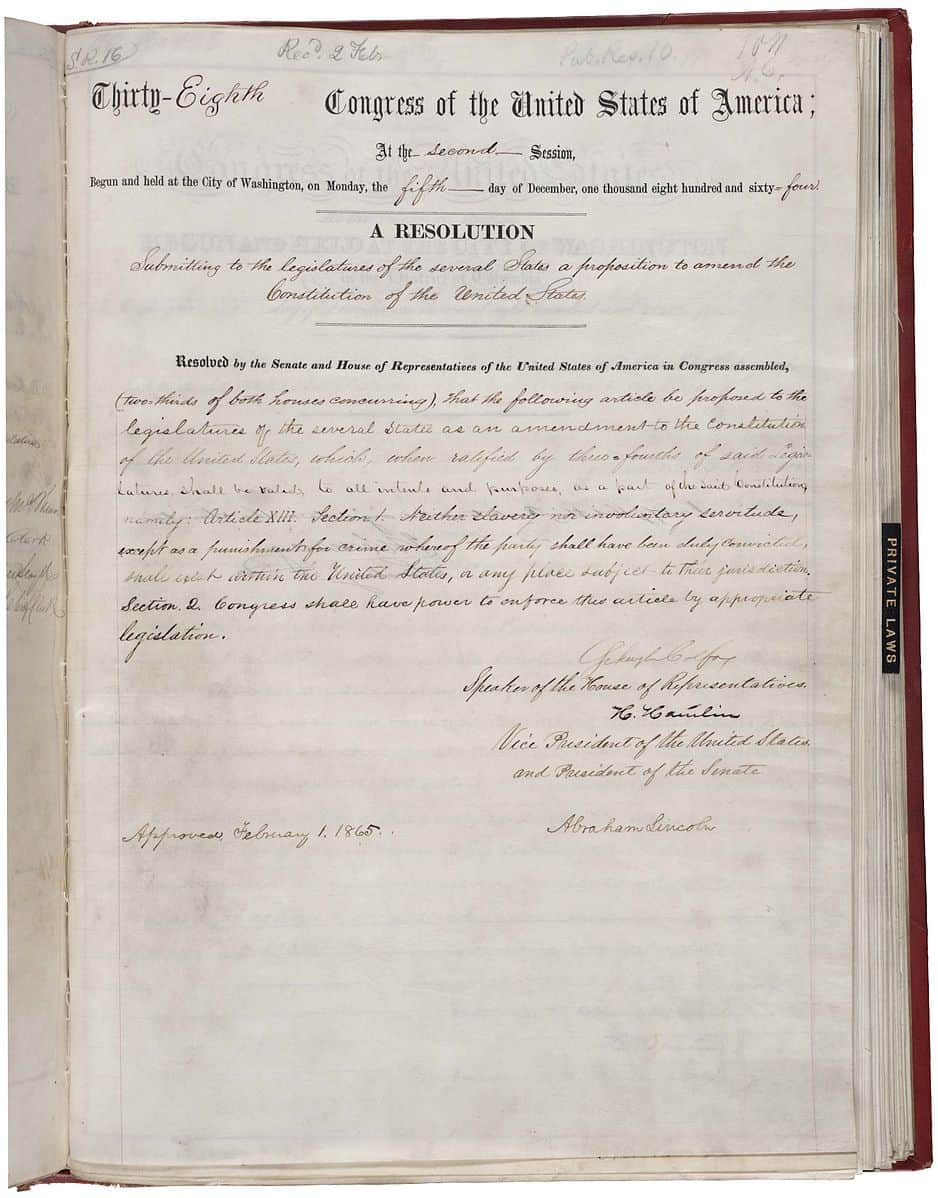

Advocates challenging forced labor practices are largely relying on the Trafficking Victims Protective Act (TVPA). However, as Leora Smith noted, the Thirteenth Amendment is “[l]urking in the background of [these] case[s].” Smith posits that advocates may be reluctant to bring Thirteenth Amendment claims due to the complicated case law around what constitutes “involuntary servitude.” These complications have not gone unnoticed by scholars. In her article Unlucky Thirteenth: A Constitutional Amendment in Search of a Doctrine, Lauren Kares observes that “the Thirteenth Amendment is notable for its lack of a coherent jurisprudence.” This post takes a closer look at the odd set of exceptions to the Thirteenth Amendment, paying particular attention to what some lower courts refer to as “the civic duty exception.”

In Pollock v. Williams, the Supreme Court reaffirmed that “[t]he undoubted aim of the Thirteenth Amendment…was not merely to end slavery but to maintain a system of completely free and voluntary labor throughout the United States.” However, the Court continued, “[f]orced labor in some special circumstances may be consistent with the general basic system of free labor.”

The text of the Thirteenth Amendment explicitly excepts labor compelled as punishment for a crime from its purview. A few other exceptions for “special circumstances” have been read into the Amendment by courts. They include work compelled of children by their parents or apprenticeship masters and another category of services historically treated as exceptional. The latter exception has been amorphous and ill-defined since its inception.

The Court first found such an exception in the 1897 case Robertson v. Baldwin, holding that the contracts of seamen do not fall within the “spirit” of the Thirteenth Amendment. While this exception seems odd today, the Court explained that “[f]rom the earliest historical period the contract of the sailor has been treated as an exceptional one, and involving, to a certain extent, the surrender of his personal liberty during the life of the contract.” The Court then provided a lengthy accounting of this exceptional treatment.

The Court found another exception in the 1916 case, Butler v. Perry. According to Butler, able-bodied men may be compelled “to labor for a reasonable time on public roads near [their] residence without direct compensation” because it “is a part of the duty which [they] owe to the public.” The Court explained that certain services have “always [been] treated as exceptional” and that the Thirteenth Amendment was “certainly…not intended to interdict enforcement of those duties which individuals owe to the state, such as services in the army, militia, on the jury, etc.” Again, the Court provided a lengthy accounting of the historically exceptional treatment of work on public roads, this time tracing back to the ancient trinoda necessitas of Anglo-Saxon times.

As previewed in Butler, the Court later found exceptions for two similar “public duties:” military service in Selective Draft Law Cases (1918) and jury service in Hurtado v. United States (1973). Later, in United States v. Kozminski, the Court characterized these cases, along with Butler, as a class of cases recognizing “that the prohibition against involuntary servitude does not prevent the State or Federal Governments from compelling their citizens, by threat of criminal sanction, to perform certain civic duties.” However, notably, this characterization was merely dicta; the Court noted that “such exceptional circumstances” were not present in the case.

Like the majority in Kozminski, some lower courts have taken up the Court’s language about “public-” or “civic duties,” leading them to find a broader swath of exceptions. For example, in United States v. Ballek, the Ninth Circuit concluded “that child-support awards fall within that narrow class of obligations that may be enforced by means of imprisonment.” Relying on Butler’s language about “duties which individuals owe to the State,” the Ninth Circuit reasoned that child-support obligations must be exempt, in part because of the state’s “interest in protecting the public fisc by ensuring that the children not become wards of the state” and because of the matter’s “vital importance to the community.” Professor Noah Zatz discusses the potentially far-reaching implications of Ballek in his 2016 piece for the Seattle University Law Review.

Similarly, the Fifth Circuit and the Supreme Court of Indiana have extended the “civic duty exception” to housekeeping tasks in public institutions. Also citing Butler, the Supreme Court of Indiana held in Bayh v. Sonnenburg that requiring patients at a mental health facility to perform housekeeping tasks “fit squarely within this ‘civic duty’ exception.” Later, in Channer v. Hall, the Fifth Circuit held that requiring a civil detainee to work in the detention center’s Food Services Department fell within the Amendment’s exception. (The Second Circuit appears to disagree in McGarry v. Pallito.)

A few lower courts have concluded that school work requirements fall within the exception. In Bobilin v. Board of Education, State of Hawaii, the District of Hawaii held that “[o]n the basis of the balances that the Supreme Court has struck in the past—its weighing the duties and impositions mandated by law against the public need served—it is manifest to this Court that the cafeteria duty here imposed by State regulations do not fall within the proscription of the Thirteenth Amendment.” The Eastern District of Pennsylvania followed Bobilin in Steirer v. Bethlehem Area School District, finding a high school’s community service requirement exempted.

While these lower court cases rely on Butler and other Supreme Court cases, the courts’ brief references to public and state interests stand in stark contrast to the Court’s lengthy accounting of historical exceptional treatment of the practices at issue in Butler and Robinson. Despite the attractiveness of exempting certain practices of “vital importance to the community,” courts should be cautious about the extension of this exception. Such expansions are inconsistent with the Supreme Court’s narrow, careful carve-outs and threaten to undermine the “undoubted aim” of the Thirteenth Amendment, as articulated in Pollock, “to maintain a system of completely free and voluntary labor throughout the United States.”

Broadening the scope of the civic duty exception creates a line drawing problem identified in Robertson, where the Court explicitly rejected the idea of a broad-sweeping exception for “public service.” The Court observed: “To say that persons engaged in a public service are not within the amendment is to admit that there are exceptions to its general language, and the further question is at once presented, where shall the line be drawn?”

In resolving this question, lower courts should return to the wisdom of Robertson. The Court continued, “[w]e know of no better answer to make than to say that services which have from time immemorial been treated as exceptional shall not be regarded as within its purview.”

Daily News & Commentary

Start your day with our roundup of the latest labor developments. See all

April 18

Disneyland performers file petition for unionization and union elections begin at Volkswagen plant in Tennessee.

April 18

In today’s Tech@Work, a regulation-of-algorithms-in-hiring blitz: Mass. AG issues advisory clarifying how state laws apply to AI decisionmaking tools; and British union TUC launches campaign for new law to regulate the use of AI at work.

April 17

Southern governors oppose UAW organizing in their states; Florida bans local heat protections for workers; Google employees occupy company offices to protest contracts with the Israeli government

April 16

EEOC publishes final regulation implementing the Pregnant Workers Fairness Act, Volkswagen workers in Tennessee gear up for a union election, and the First Circuit revives the Whole Foods case over BLM masks.

April 15

The Supreme Court ruled in favor of bakery delivery drivers in an exemption from mandatory arbitration case; A Teamsters Local ends its 18-month strike by accepting settlement payments and agreeing to dissolve

April 14

SAG-AFTRA wins AI protections; DeSantis signs Florida bill preempting local employment regulation; NLRB judge says Whole Foods subpoenas violate federal labor law.